I first knew about Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun from a video by National Gallery. My first impression is that this women is a bold yet feminine painter. She rose from a modest background, and painted without academic training or public acknowledgement and became a kind of ‘celebrity’ artist. To me, she is a true feminist: she never stopped embracing her tender, maternal character in her painting; yet in real life, she fought in her own way to be able to do the things she loved.

(Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

She wrote about her youth in her autobiography and her love for arts started from when she was a schoolgirl. Her father had always seen something in her and let her play with his crayon pastels all days. She never admitted she was gifted to be painter, but declared “what an inborn passion for the art I possessed. Nor has that passion ever diminished; it seems to me that it has even gone on growing with time, for to-day I feel under the spell of it as much as ever, and shall, I hope, until the hour of death.” (1)

This passion never left her for all her life. She painted portraits professionally from early teens without a license from the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Academie for short). This was not a surprise, considering the Académie’s position of monopoly on the art market. A female artist wasn’t allowed to attend figures classes with naked models. Élisabeth wasn’t trained formally, mostly self-taught and guided by mentors who were friends of her father: Hubert Robert, Joseph Vernet, etc.

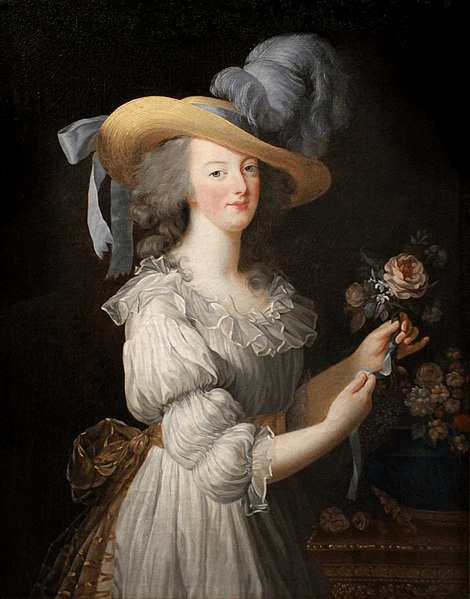

She rose to be the favorite court painter of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, wife of Louis XVIII. The queen, with the king, intervened to help Élisabeth get a license. She developed a friendship with the queen, which was unusual considering their classes. In her memoir, Élisabeth shared about the kindness she was given by the queen and their mutual interest in music. (1) The life of the two women paralleled and contrasted in a curious way, pairing with the fluctuations of French politics.

She was friends and acquaintances with many aristocrats, and she became a salonnière, simply explained, she hosted social gatherings for people to talk about arts, literature, history, politics, etc. Salons were mainly hosted by women, namely Madame de Tencin, Madame du Deffand (friend of Voltaire), Madame Necker (wife of Louis XVI’s director of finances). Still, Élisabeth painted furiously at day and hosted sessions of poetry readings or musical recitals at night. She never wanted to be known as a salonnière, the point of opening a salon was to support her passion and her husband’s career as an arts dealer.

She reached her peak from 1783 till 1789, after she received official admission from the Academie. In 1783, she also finished the painting known as “Marie-Antoinette en gaulle”, in which she depicted the queen in a close and intimate point of view. Élisabeth wanted to represent the queen not just as a queen but a women “in all her appealing and vulnerable femininity”. (2) In 1783, 1785, 1787, and 1789 Salons, she achieved great success with her portraits of royal members and her own family. In total, she submitted more than fifty pictures. (3)

These glamourous days ended in 1789, the outbreak of French evolution. Her most important patron and friend, Marie Antoinette was executed in 1793. Élisabeth fled to Rome, Italy and then Saint Petersburg, Russia. She was patronized by royal members and kept painting them to support herself and her daughter, Julie. Her financial situation was bad despite her success. The money she earned in her teen years was used up by her step father, and the money she earn after marriage was used up by her husband (2). She returned to Paris in 1802, officially separated from Le Brun in 1805, and he passed away in 1813.

She continued to paint until the day she died in 1842, as she hoped in her youth. In 1835, Vigée Le Brun published her memoirs titled “Souvenirs,” which told the story of her life from very early days until the last moment.

What’s admirable about Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun is her hard-working and brave attitude to stick to her passion. She is the true definition of “pursuing passion” and her love for arts became what kept her alive in difficult times. She was a protégée, but as a women, she had to overcome many more obstacles just to be recognized. Her hard-working attitude shines from her memoir.

She experienced ups and downs in both her social and private life. She became the most sought for-female portraitist in Paris, yet she was forced to get married and didn’t have a happy personal life. She lived a long life (she passed away at 86 years old) and her admirers surrounded her till the end, yet she suffered the loss of her only daughter, her close brother, her friends. She witnessed the monarchy reaching its peaks and collapsing to dust. Her portraits, her memoir are now evidences of a remarkable era of French history.

Her memoir is available for free on Project Gutenberg .

(1) Vigée-Lebrun, Louise-Élisabeth. Memoirs of Madame Vigée Lebrun. Translated by Lionel Strachey. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1903.

(2) May, Gita. The Odyssey of an Artist in an Age of Revolution. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

(3) “The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842).” Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed July 10, 2024. URL: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/vgee/hd_vgee.htm.

Discover more from Jeanne Lolness

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.