If you have read my blog about Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, chances are that you enjoy this article about Adélaïde Labille-Guiard – a fellow female artist. They are two of only four females accepted into the Academy in 1783. Critics at the time liked to portray them as contemporary rivals, since they had many in common. However, there is no solid evidence of rivalry or friendship, since formal history often doesn’t take relationships and feelings into account. One concrete fact is that both female artists have supreme talents and suffered from male jealousy to political fluctuations in 18th century.

A calculated career

Adélaïde didn’t have any artistic family background, she was one of eight children born to a Paris shopkeeper. Despite that, she turned to artists in her neighborhood, first painting miniatures with Francois-Ele Vincent, then working with pastel taught by Maurice Quentin de La Tour and then Francoi Andre Vincent (son of Francois – Elie). She worked her way up the academia art world gradually, from joining the Academia de Saint Luc, exhibiting at the Salon de la Correspondance and finally the Academia Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. While Vigee-Le Brun was preferred by the Queen, Adelaide painted King Louis XVI’s aunts, Mesdames Adelaide and Victoire along with a wider range of topic.

pastel on blue paper mounted on canvas;

28.74 x 23.14 in (730 x588 mm)

However, she couldn’t have planned for the French revolution. She welcomed the Revolution and supported with ‘“patriotic donations”. However, the subjects of her previous portraits became the liabilities, attracting criticism from men and even danger. The post-revolutionary successor to the Academy decided to exclude woman from the art world. The Directory of the Department of Paris required Labille-Guiard to hand over an enormous group portrait, commissioned by the king’s brother to burned. She saught refuge in the countryside and only returned to Paris in 1795 and die in 1803. If there was anything from the Revolution benefiting her, she was able to divorce her husband, Louis Nicholas Guiard and married her rumored to be lover and teacher, Andre Vincent in 1800. (Auricchio (2009))

Pastel on blue paper, seven sheets joined, laid down on canvas,

Oval, 31 x 25 3/4 in. (78.7 x 65.4 cm.)

A feminist

Despite her formal education and training, she was greeted with controversy and rumors. Vincent, who was rumored to be her lover at the time, was said to have ‘touches up’ Labille-Guiard – an offend towards both her paintings and personal life. (more: “His love makes your talent. Love dies and talent falls”). More ridiculous tales including her 2000 lovers were only stopped after her appealing to a well-placed patron, who was possibly the wife of the director of the Batiments du roy. She was outraged, of course: “One must expect to have one’s talent ripped apart”. (McPhee (2021))

In the argument in the Academy on contributing to the regeneration of the nation, she was the only woman, naturally attracting criticism. (Auricchio (2009)) She proposed increasing numbers of women being admitted to the Academy, but was rejected. Despite the term revolutionary with his name, Jacques Louis David, emphasized: “The rewards destined for artists cannot be without danger for woman [since art requires] long and hard study … incompatible with the modest virtues of their sex”. (McPhee (2021))

She had always dreamt of establishing a school for female artists, which can be seen in her most important work “Self-Portrait with Two Pupils”. Besides her foremost position as her prestigious artist for the royal family, she expressed herself as the educator and supporter for female artists. One of the students shown was Marie Gabrielle Capet, her favorite students and another talented artist. Both shared the dream of a school for female artists and lived together even after the marriage to Vincent. After A’s death, Capet kept taking care of Vincent.

An educator

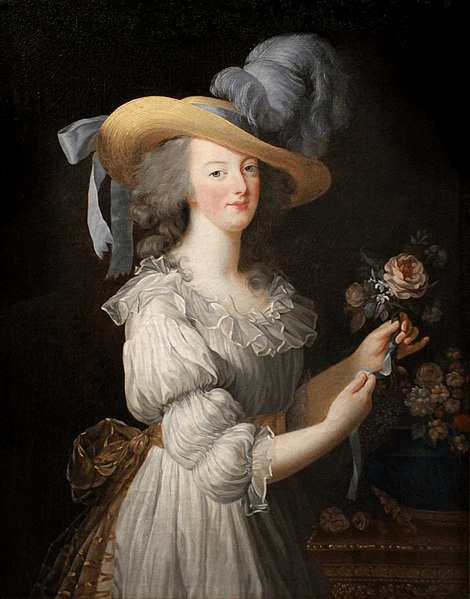

Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie Gabrielle Capet and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond , 1785

Oil on canvas; 83 x 59 1/2 in. (210.8 x 151.1 cm)

In the painting “Self-Portrait with Two Pupils,” she chose to show herself in a fashionable dress and a straw hat, not quite the style expected in an artist’s studio. Let’s not forget that she grew up with fabrics around, and she tended to indulge in the latest fashion in her works. She appeared to be wearing robes à l’anglaise, “fitted close to the waist in the front and back.”(Fashion History Timeline (Klopfer, n.d.)) She dressed herself in the latest fashion of a low plunging neckline and revealing bust line, which is similar to Vigee Lebrun’s portrait of Marie Antoinette. Along with two other females who dressed completely distinguished form each other, the purpose of dress choice was possibly to showcase her expertise in rendering cloth, especially the latest fashion in society.

Her silk dress’s pastel blue color also reflected the characteristics of the Rococo style. She was over 30 years old, married, and had been working for more than 10 years when the painting was made.

In the portrait, she and one of her students, Marie Marguerite Carreaux, smiled and looked directly at the audience, while Marie Gabrielle Capet was staring at the canvas. Carreaux was possibly wearing a chemise dress, which was usually seen with the straw hat outside rather than inside a studio. Capet, on the other hand, was dressed in what resembled the attire of a female artist working in her environment. Her lighting rendering skill was shown here, with Capet’s youthful face was softly lit, while Carreaux was almost entirely in the dark. (Fashion History Timeline (Klopfer, n.d.))

Black chalk with stumping, red and white chalks on beige paper

One notable thing is the straw hat, an object didn’t go well with any dresses or the indoors studio. Pairing a formal fashionable dress with a straw hat could indicate that Adélaïde didn’t see herself as completely belonging to the fancy world of the royals. In fact, her dress was the only ‘fancy’ thing in a simple studio.

Compared to other portraits by her and a self-portrait by her contemporary, Vigee Le Brun, she didn’t include any flowers but chose to include a sculpture of a vestal virgin and a bust of their father. This could reflect her modesty and indicate that her final goal was to attain the same status as the males in the Academy who painted historical scenes—the most important genre at the time.

The stick she is holding supports this notion; it was more likely that she was working on a grand scene rather than portraits and still lifes, which were more suitable for females. This was a bold goal for a woman, but with her students present, she likely aimed to push more female artists into the limelight alongside her own achievements.

In the end

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard’s dream didn’t come true, there was no art school for female artists nor there were more females in the Academy. Nevertheless, her life and work embody resilience, talent, and a progressive vision for women in the arts. Despite facing societal prejudice, political upheaval, and personal challenges, she carved out a place for herself in the male-dominated art world. Her advocacy for female artists, exemplified in her iconic Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, highlights her dedication to empowering women and redefining their roles in artistic academia. Labille-Guiard’s legacy serves as an enduring reminder of the barriers she broke and the paths she paved for future generations of women in art.

References

Auricchio, L. (2009). Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. Harvard Magazine. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2009/09/adelaide-labille-guiard

Klopfer, M. (n.d.). 1785 – Labille-Guiard, self-portrait with two pupils. Fashion History Timeline. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1785-labille-guiard-self-portrait

McPhee, P. (2021). Hidden women of history: Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, prodigiously talented painter. University of Melbourne. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/news/3011-hidden-women-of-history–ad%C3%A9la%C3%AFde-labille-guiard–prodigiously-talented-painter

National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA). (2021). Royalists to romantics: Spotlight on Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://nmwa.org/blog/artist-spotlight/royalists-to-romantics-spotlight-on-adelaide-labille-guiard

Louvre Museum. (n.d.). Portrait of Madame Adélaïde [Painting]. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl020212847

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met). (n.d.). Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Self-portrait with two pupils [Painting]. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436840

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met). (n.d.-b). Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Portrait of Madame Adélaïde [Painting]. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/439405

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met). (n.d.-c). Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Portrait of a woman in profile [Painting]. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/335183

Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.-a). Labille-Guiard, A. (1787). Marie Adélaïde de France [Painting]. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Labille-Guiard,_Ad%C3%A9la%C3%AFde_-_Marie_Ad%C3%A9la%C3%AFde_de_France_-_Versailles_MV5940.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

Wikimedia Commons. (n.d.-b). Capet, M. G. (1808). Atelier of Madame Vincent [Painting]. Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marie-Gabrielle_Capet_-_Atelier_of_Madame_Vincent_-_1808.jpg#mw-jump-to-license